On the Work of Christopher D’Arcangelo, 1975-1979

Heather Davis + Michael Nardone

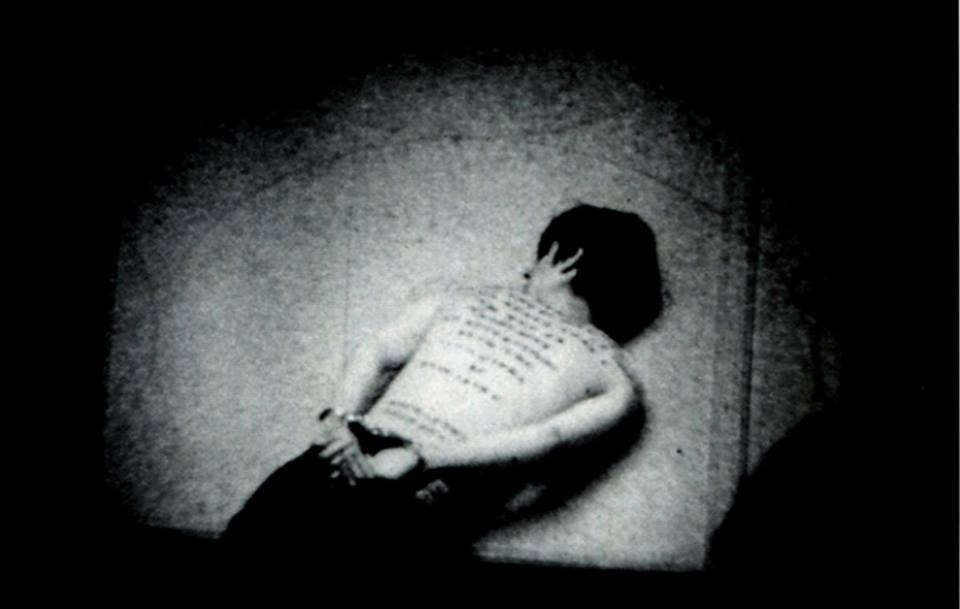

“Anarchism without Adjectives” has responded to D’Arcangelo not by mounting a retrospective of his work or archives, but by engaging with the numerous questions his practice provokes. These questions – of documentation, of institutional critique, of the relation of labour to art production, and of the possibility for art to engage directly with political discourse – remain crucial for contemporary art practice. The exhibition at the Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery is the fifth iteration of the show and presented works activated by D’Arcangelo’s museum interventions, and labour series that focused on the physical construction of exhibition spaces (produced with Peter Nadin). Curators Dean Inkster and Sébastien Pluot, working in collaboration with Michèle Thériault, have put together an extensive and diverse array of conceptual work that speaks to the legacy of D’Arcangelo, while drawing on the context of Montreal.Here, the only remnant of D’Arcangelo’s actual oeuvre was found at the entrance to the exhibition, mounted as a simple list of his collected works. Directly inside, six video interviews – with Peter Nadin, Ben Kinmont, Lawrence Weiner, Benjamin Buchloh, Daniel Buren, and Naomi Spector with Stephen Antonakos – form an oral history of D’Arcangelo. They operate as a living archive: friends, critics, and contemporary artists relay rumours and stories, just as the take up of the works by contemporary artists in the show could be understood as the passage of his practice through time. These videos present the most compelling aspect of the show for those directly interested in D’Arcangelo, offering a broader sense of his project and displaying the ongoing critical interest in his work with the attending questions and anxieties that continue to resonate in art practice today.While this transmission from D’Arcangelo into contemporary practices is evident in all the works, it is explicitly taken up by Ben Kinmont and Sophie Belair Clément. As an homage to the artist, Kinmont publicly published a book of interviews and archival material on D’Arcangelo to be distributed to passers-by outside the Louvre. The site references D’Arcangelo’s 1978 intervention at the museum in which he removed a Gainsborough painting from the wall, “reinstalling” it nearby upon the floor, and posted upon the bare wall space a statement that asked “When you look at a painting, where do you look at that painting?” Clément’s installation includes a reconstruction of the Louvre wall with its absent Gainsborough painting and a video presenting a chronology of D’Arcangelo’s actions that he may or may not have done.

While Pierre Bal-Blanc’s video lecture “Tomorrow I Go to the MoMA” (2012) addresses the many challenges in documenting intervention, performance and labour works, Pierre Leguillon’s projection of D’Arcangelo’s textual intervention “LAICA as an Alternative to Museums” (1977) makes visible the blank page in which D’Arcangelo invited viewers to exert their own “curatorial control.” Sylvia Kolbowski’s “An Inadequate History of Conceptual Art” (1998-9) presents a series of interviews with conceptual artists, focusing only on their hands, while the sound plays asynchronously with the video. The artists interviewed were asked to avoid reference to all proper nouns – titles, place names, names of artists – drawing attention to a system of art production and circulation that seeks to place the name of the artist as the missing commodity.

Rainer Oldendorf’s and Émilie Parendeau’s documentary pieces establish a more expansive sense of D’Arcangelo’s historical present. Taking from his personal archive, Oldendorf has constructed a wall of photocopied personal and public texts and images from the years 1975-79, the working period of D’Arcangelo. Parendeau’s “Artist as Assistant” creates a space in which one can view a selection of readings on the numerous artists’ works that D’Arcangelo laboured as an artist’s assistant.

The works of Montreal-based artists François Lemieux and Simon Brown as well as Nicoline van Harskamp begin to move away from D’Arcangelo toward a more direct consideration of anarchism. Lemieux uses the analogy of a loosely tied raft in his poem “Et la télévision inventa le samedi matin,” (2013) to beautifully illustrate the relations of anarchist practice today. Composed of both original and sourced language, the text (available as give-away multiples at the desk, while the references are framed on the gallery wall) engages with contemporary paradoxes of movement building. Brown’s zine-like publication “Chris, Simon & Jennifer,” (2013) is the only piece that directly references the 2012 Quebec student uprising. Alluding to D’Arcangelo’s museum shacklings on its cover, the work portrays the frequent brutality of the Montreal police in response to student demonstrations.

Van Harskamp’s “Yours in Solidarity” (2013) is a multi-faceted work based on the letter archive of late Dutch anarchist Karl Max Kreuger. For over ten years, Kreuger corresponded with a global network of individuals on political issues. Several letters from this archive, hand-copied by van Harskamp, appear framed on a gallery wall. Beside them, two subtitled audio tracks document van Harskamp’s collaboration with actors to develop characters based on the details and perspectives of the letters’ authors. Once developed, van Harskamp staged and filmed a fictional meeting of what might happen if all the characters were to meet one another in one space today. The outcome is a stunning portrayal of the duration, dissonance and occasional consensus of direct political engagement.

This show captures well the paradoxical relationship between D’Arcangelo’s guiding concept of anarchism and the institutional constraints of contemporary art. As Thériault commented, in the aftermath of the student uprising in Québec, people are interested in art that could directly address questions of political engagement. “Anarchism without Adjectives” points to both this desire while illuminating its distanciation due to its institutional framings. However, as D’Arcangelo himself wrote in his 1975 notebook, “It is not the paradox but the space between the two parts of the paradox that is important.”

+

Originally published in Camera Austria 124, 2013.